PEF; tech stocks

private equlity generates so much debt, which is a global threat

“How private equity tangled banks in a web of debt”

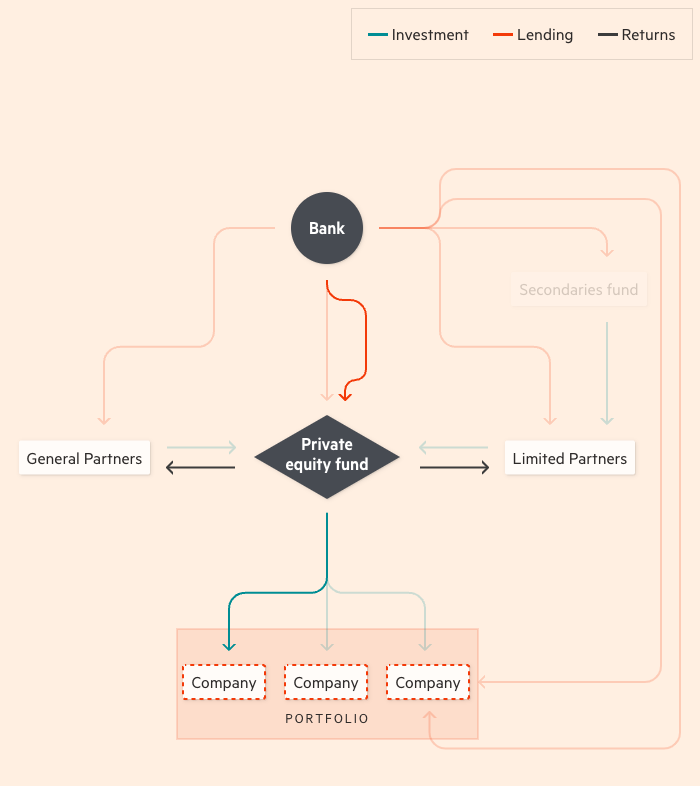

Private equity grew through the low-interest environment, which enabled them to purchase firms easily. In the process, banks constructed multiple connections with the actors of PEFs such as “ending to buyout-owned companies, the funds that acquire them, the firms that manage them and the investors that back them.”

- interest rate hikes can upend all this, posing essentially a big risk to banks.

So how does a PEF operates (to by companies), ending up affecting banks?

- At the beginning, a PE firm will launch a fund with partners (executives), who are “responsible for managing the fund.” Limited partners (outside investors) might pitch in some cash too. These partners may borrow from banks “to finance their commitment to the fund.” This borrowing may generate collateral, which are the partners’ “existing stakes in other funds.”

- In return, a general partner gets paid of a fee (for managing the fund) “as well as a share of the profits from successful investments.”

- What amounted to the borrowing that reaches $900 bn in 2023 is the subscription line: “short-term financing used to acquire companies before cash from limited partners is tapped.” The money from limited partners is used as security for a subscription line. But a subscription line plays only a partial role

- The primary resource to complete a company-buying deal is simply debt financing (borrowing) from banks. The cash generated by the business of the bought company is used to pay off this debt. This debt might be sold to others, but the bank has to hold on to it if the demand is weak.

- PEFs will repeat the process of 1-3 and end up owning multiple companies (or a portfolio of companies). Using these companies as collateral, the fund can also borrow<> directly from banks. Such money can either bail out a struggling company (which is a ‘leverage on leverage’) or fund a payout to investors (net asset value financing: $100 bn in 2023). Overall a high-leverage structure.

- ‘Secondaries funds’ can buy stakes from limited partners. For a bit of discounts, this gives limited partners some cash upfront. The secondaries may also borrow from the bank to finance this.

- Individual companies (owned by PEFs) may also borrow directly from bank to boost returns for investors. (this borrowing reached $30 bn in 2024)

- ‘General partner stakes funds’ can buy the funds’ stake directly from general partners. To fund this purchase, they may also borrow> from banks.

Some big examples of this kind of buyout model: Caesars Entertainment (casino); Alliance Boots (pharma chain)

some big PE firms specialized in this kind of processes (secondaries fund): Blackstone, Ardian. Other financial actors buy shares of this kind of PF firms.

In a high interest rate environment, all these borrowings add up. And partners seek more liquidity upon growing pressure, initiating a negative spiral.

‘Private credit funds’ also have been lending just like banks. They have much less transparency or liquidity than banks. But because they are lending to the same actors/actions as the banks do, a shock emanating from the private credit market will shake banks.

Tech stocks sink.

“Global tech stocks sink as sell-off spreads to Europe and Asia”

“Global tech stocks sank on Thursday as a Wall Street sell-off spread to Europe and Asia.”; “The Nasdaq Composite fell 0.8 per cent after the opening bell on Wall Street, extending its recent slump following the worst day in 18 months.”

Chipmakers (Nvidia and Arm Holdings) led the downward trend. Disappoint earnings reports and geopolitical tensions are said to be the culprits. German, Japanese (particularly dramatic), and South Korean chipmakers stocks also showed similar patterns.