South Korea: The Case of A Long Democratization

The Shock

The latest insurrection attempt by Yoon Seok-yeol of South Korea stunned the world. It was widely believed that this affluent democracy with its cherished soft power would not be subject to a sudden political upheaval. After all, South Korea is far above the structural ‘thresholds’ that political scientists have long reported, be it Argentine GDP in 1975 or two decades of years beyond which a democratic regime might not fall.

Many have already offered extensive accounts on a litany of ways in which Yoon’s declaration of martial law was unconstitutional and constitutes, in essence, an insurrection, self-coup, and/or a treason. This and this as well as, you know, my own might be helpful explainers. It’s hard to miss the whiff of anger, fury, or terror in them.

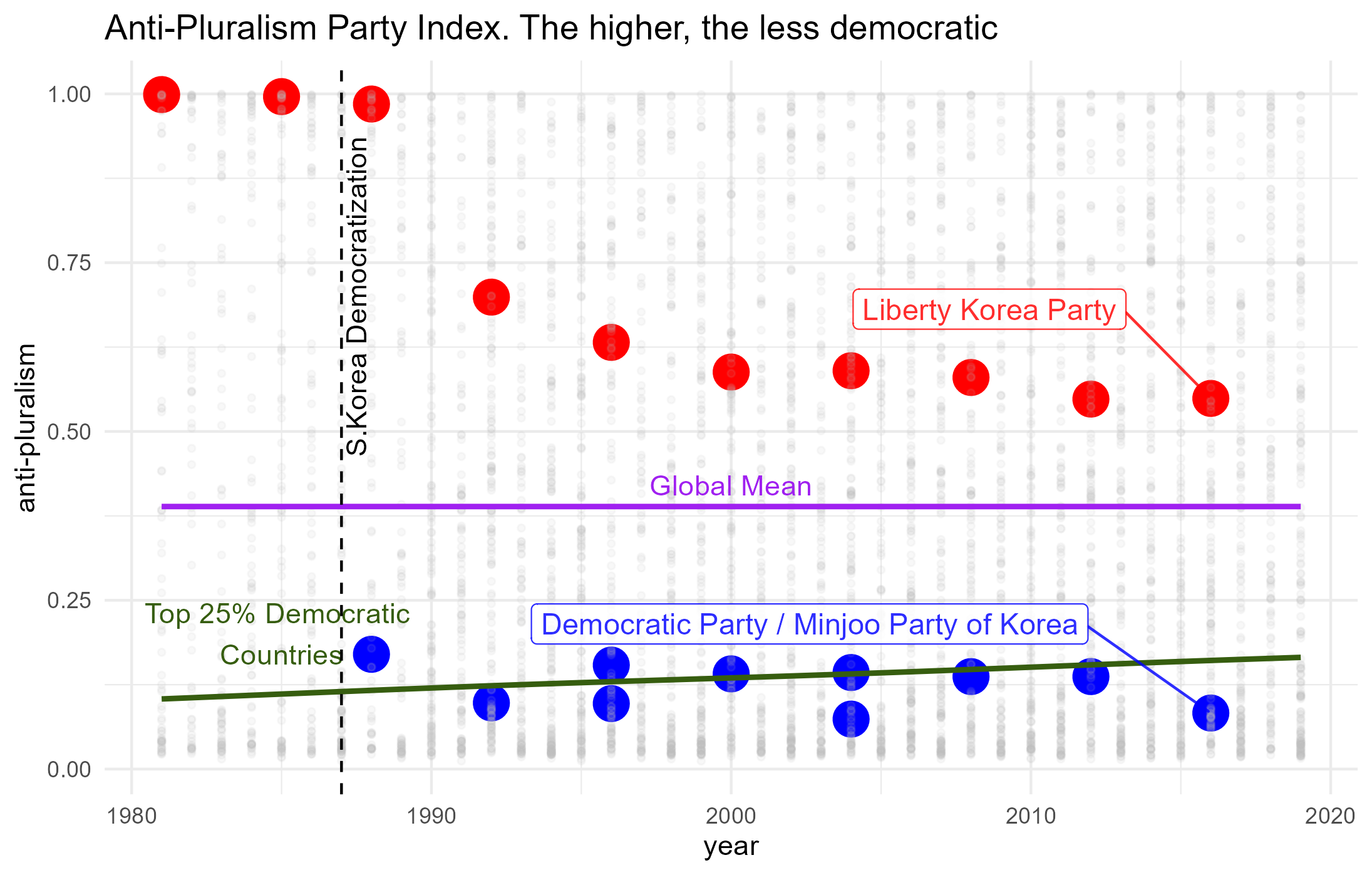

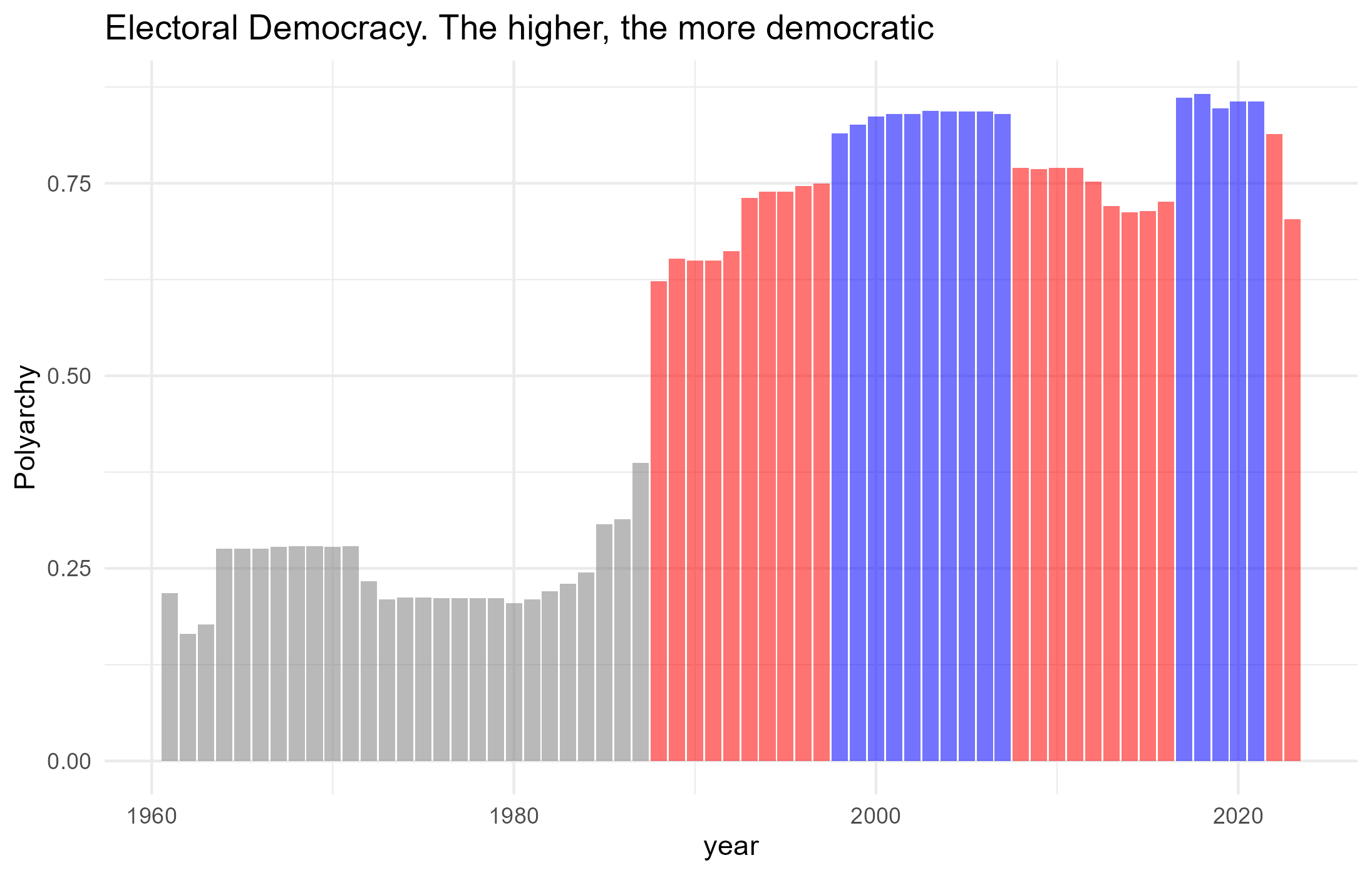

There is one assumption common in these understandable reactions–that South Korea was (nearing) to achieve the status of a consolidated democracy. Perhaps, its democratic regime was becoming so entrenched and irreversible that it is “the only game in town”. Indeed, since the democratization in 1987, the hard-earned democratic institutions and organized citizens consistently prevailed over a series of crises–no way it could be suddenly derailed!

Unless, of course, that assumption could be questioned. What if the post-1987 Korea never amounted to democratic consolidation where any serious danger of collapse was reasonably negated? What if, instead, serious threats were always lurking around the society? What if, when those threats occasionally manifested themselves, they were not taken seriously enough?

And an even more important to question to ask is: if the existence of these threats is verified, what needs to be done now in order to avoid repeating another insurrection?

Democratic Survival vs. Consolidation

Milan Svolik demonstrates that democratic consolidation and democratic survival are two different factors. Institutional factors (presidentialism and previous military dictatorship) make a transitional regime susceptible to reversal, but the immediate trigger is a recession. As in:

“[L]ow levels of economic development, a presidential executive, and a military authoritarian past reduce the odds that a democracy consolidates. However … the eventual timing of reversals is associated only with economic recessions.”

This framework offers at least a fairly convincing ‘partial’ explanation of what happened in South Korea. Two of the three factors–presidentialism and previous military dictatorship–feature prominently in the current case. First, the South Korean presidential system is often referred to as ‘imperial,’ in that presidents enjoy an wide array of discretionary de facto powers. The legislative and judicial bodies of the government have only limited recourse to constrain these powers. For instance, in theory, the president can torpedo any legislative initiatives as far as the ruling party has 1/3 of the seats. Yoon used this abused this authority to a record number of times (27), setting up the political ‘confrontation’ he himself identified as one of the excuses for his declaration of martial law.

The ‘imperial’ presidentialism in South Korea: political parties not committed to democratic processes and instead function as a vehicle to solidify the power of the president. The Republican Party (Gonghwa-dang) during the Park Chung-hee regime and the Democratic Justice Party (Minjeog-dang) during Chun Doo-hwan’s.

Combination?: A Korean president also has nearly unchecked authorities over the use of military power. Yoon established a small, but powerful and effective, network of generals composed of his own cronies, many of whom he went to the same high school with. He then used this network as a source of violence needed to mount the coup, albeit unsuccessfully.

The country also suffered from highly oppresive military dictatorship for almost three decades. Both Park Chung-hee (1961-1979) and Chun Do-hwan (1980-1987) conjured various military apparatuses to secure their rule via coercive and violent means. During the military rule, secret military police, counter-intelligence units, and special forces were nurtured to meddle wit the civil society such that any revolutionary movements could be (pre-emptively) rooted out.